On the afternoon of April 26, 1937, the small Basque town of Guernica was subjected to a devastating aerial assault that would change the course of history. Wolfram von Richthofen and Vincenzo Velardi, commanders of the German and Italian air forces, respectively, saw an opportunity to test the destructive power of behind-the-lines airplane maneuvers. Inspired in part by the aerial doctrine of Giulio Douhet, an Italian army officer who foresaw the power of targeted bombardment in his 1921 book “The Command of the Air,” they turned Guernica into the first instance of deliberate mass bombing of a civilian population.

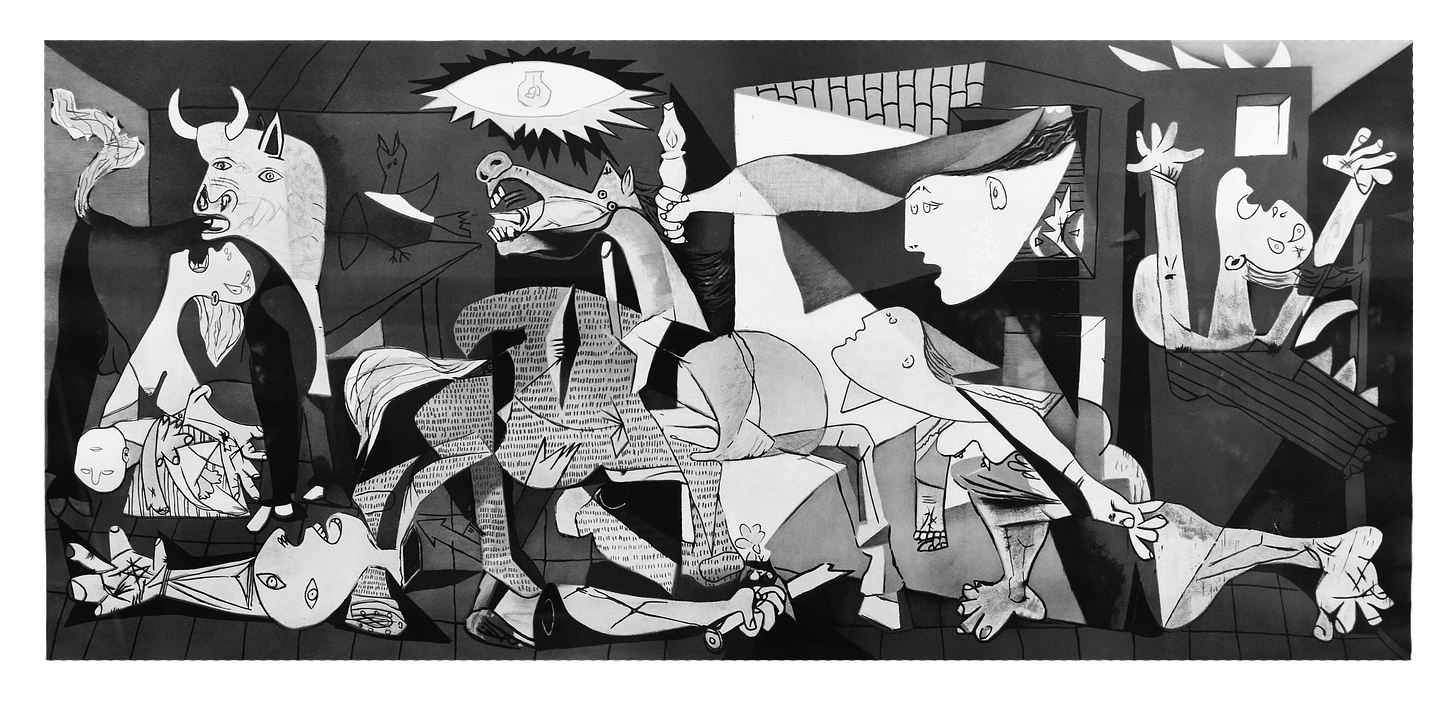

The casualties that day in the city — hundreds of civilians dead and 85% of the town’s buildings destroyed — would pale in comparison to bombing raids across Europe and the Pacific in the following years. Nonetheless, the destruction of Guernica would foreshadow the sharpened brutality of modern warfare. It marked a turning point where the line between combatants and civilians blurred, and the act of killing became more distant and dehumanized under the auspices of new technologies. The event would soon dominate headlines and inspire one of the greatest anti-war works of art in history, Pablo Picasso’s monumental painting, Guernica, inspired by his partner at the time, the prominent anti-fascist activist Dora Maar.

Gaza, one of the most extensive testing grounds of AI-enabled air doctrine to date, is today’s equivalent of Guernica in 1937. Over the past year of conflict, it has become the latest testing ground of breakthrough warfare technologies on a confined, civilian population — and a warning for more atrocities to come. The Israeli Defense Forces’ use of American bombs and AI-powered kill lists generated, supported, and hosted by American AI software companies has inflicted catastrophic civilian casualties, with estimates suggesting up to 75% of victims being non-combatants. Lavender, an error-prone, AI-powered kill list platform used to drive many of the killings, has been strongly linked to (if not inspired by) the American big-data company Palantir. Intelligence agents for the IDF have anonymously revealed that the system deemed 100 civilian casualties an acceptable level of collateral damage when targeting senior Hamas leaders.

Yet, instead of reckoning with AI’s role in enabling humanitarian crimes, the public conversation on the subject of AI has largely revolved around sensationalized stories driven by deceptive marketing narratives and exaggerated claims. Stories which, in part, I helped shape. Stories which are now being leveraged against the American people, in the rapid adoption of evolving AI technologies across the public and private sector — all upon an audience that still doesn’t understand the full implications of big-data technologies and their consequences.

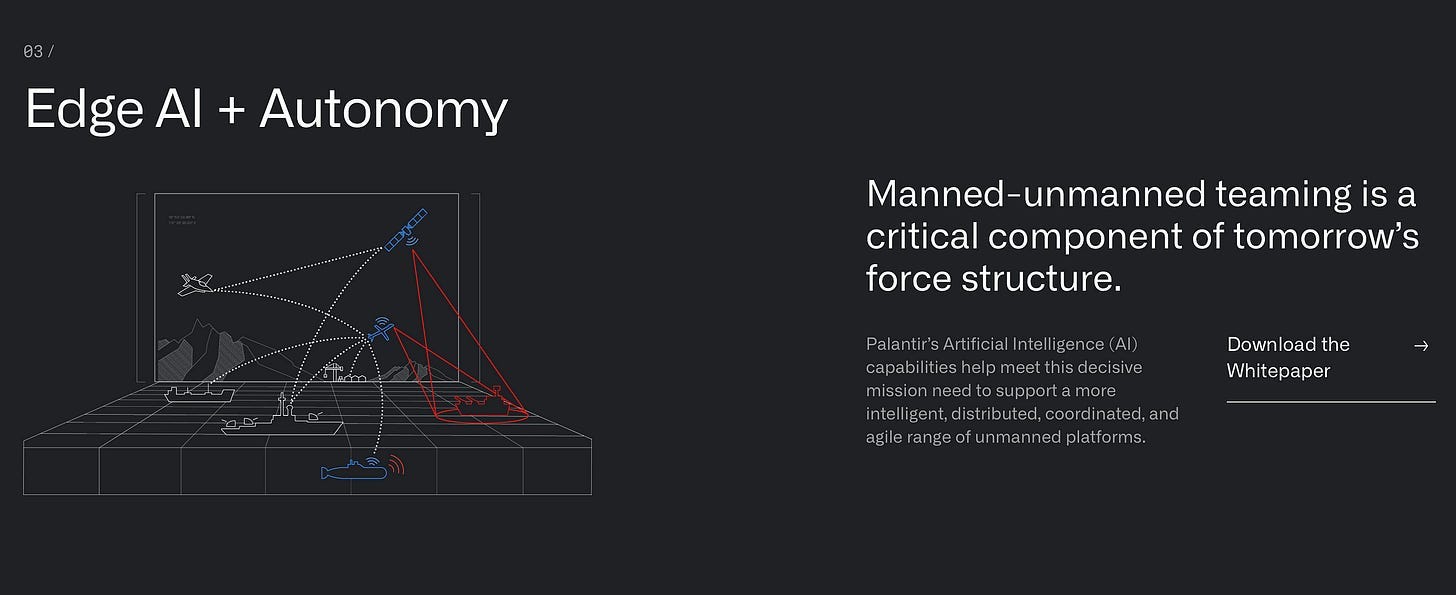

I know because — for a year and a half after the pandemic — I worked at Palantir Technologies from their new headquarters in Denver, Colorado. There I marketed their core software offerings — Gotham, Foundry, and Apollo — while also developing written materials and diagrams regarding the AI kill chain: the semi-autonomous network of people, processes, and machines (including drones) involved in executing targets in modern warfare. These technologies, which Palantir co-developed with the Pentagon in Project Maven, sought to become the “spark that kindles the flame front of artificial intelligence across the rest of the Department" according to Lt. Gen. of the United States Air Force Jack Shanahan.

But this was only the beginning. While helping my team explain the advantages of AI warfare to US defense departments, I would also simultaneously help sell AI technologies to Fortune 100 companies, civilian government agencies, and even foreign governments in a range of applications, from healthcare to sales.

For a time, I truly felt — as Palantir CEO Alex Karp recently put it — that the Palantir “degree” was the best degree I could get. That I would mostly participate in creating efficient and needed solutions to the world’s most complicated problems. However, over the course of bringing dozens of applications to market, I would soon come to a dark personal realization: The core idea underlying most commercial AI analytics applications today — and the philosophy underlying the kill chain framework in the military — is that through continual surveillance, data analysis, and machine learning we can achieve a simulated version of the world, where a nation, army, or corporation can gain competitive advantage only by knowing everything about targets and delivering results autonomously before their adversaries.

Building these competing simulations, of a factory, a battleground, a connected vehicle fleet — often called “digital twins” — is not only the business of Palantir, but of established technology players like IBM, Oracle and hundreds of new startups alike. They are all furiously staking their market share of data applications across every industry and world government, unleashing a paranoid process of comprehensive digitalization and simulation, while establishing surveillance infrastructures and “moats” of proprietary knowledge, information, and control in every market and in every corner of our lives.

In fact, the phases of the AI kill chain used to execute targets in warfare, as described in the Targeting Manual of the US Air Force — to find, fix, track, target, engage, and assess — are generally analogous to the steps many tech companies use to help deploy data surveillance and AI models on (or for) their customers.

In AI-enabled military operations today, the first phases of the kill chain — finding and fixing — focus on data collection and sensor input to identify and categorize subjects as targets, threats, or non-targets. This process relies on a vast network of open-source and classified data and AI models, alongside information collected from drones, satellites, vehicles, intelligence and personnel.

Similarly, businesses deploy invasive surveillance networks, analyzing location data, loyalty programs, third-party data, social media activity and other sources to construct detailed consumer profiles. This type of categorization, known as "fixing" in a military context, allows corporations to mark individuals for targeted action.

Tracking, the next phase, involves maintaining continuous awareness of a target. From a military standpoint, this means using advanced surveillance systems to follow a target's movements and ensure precise situational awareness in real-time. In business, this often involves constant monitoring of consumer behavior through algorithms, cookies, trackers, and manipulative engagement practices designed to predict and influence future actions.

The final stages — engagement and assessment — translate to execution and process-refinement. While the military context usually implies delivering payloads and measuring their lethality, businesses aim to control consumer behavior, driving product adoption and dependency. Both systems operate as iterative loops, refining their effectiveness through continuous feedback, machine learning and improvement — whether to achieve tactical dominance or commercial control.

The result: a technological revolution with military roots — implemented from the top down by companies like Palantir — which, in practice, serve the interests of Fortune 500 companies, the United States military and intelligence complex, and world governments like Saudi Arabia and Israel. At every stage of the process of data integration, analysis, execution, and learning described above, there are serious data quality, bias, copyright, privacy, and ethical issues, many of which have been catalogued by the AI Risk Repository at MIT, and thoroughly mapped by scholars including Kate Crawford. As she writes in in her 2021 Book, Atlas of AI:

“The military past and present of artificial intelligence have shaped the practices of surveillance, data extraction, and risk assessment we see today. The deep interconnections between the tech sector and the military are now being reined in to fit a strong nationalist agenda.”

This statement holds true of the marketing I created at Palantir, and similar work they continue to publish to this day — such as the cinematic, Michael-Bay-style ad that aired over the holidays in the Army vs. Navy game where Donald Trump and Elon Musk were in attendance. These communications mask the real-world consequences of AI technologies, stoking the fire of public confusion and with a sleek, dystopian cloak, taking advantage of marketing showmanship and military jargon to veil the real implications and consequences of AI technologies. They also leverage the learned helplessness and confusion of the public, leading us to believe that there is no other alternative to staying competitive as an economy or as a nation than relentlessly advancing, deploying, and selling AI applications.

The genocide and destruction in Gaza that we have witnessed and continue to witness is not only the latest demonstration of this doctrine of terror, but also proof of what authors and researchers on killing machines — such as Andrew Cockburn and Jathan Sadowski — have long warned about: that the material realities of AI technology in autonomous warfare do not match their promises of efficiency, humanitarianism, or competitive advantage. Nor do they fundamentally address the real systemic problems that plague our world.

Despite what AI marketing might have you believe, AI isn’t new or shiny—it’s pervasive and deeply ingrained in our lives. It’s embedded in everything, including social media platforms, wayfinding apps, dating apps, cars and even our appliances. Despite turning consumer sentiment, AI has already shaped the tools we use, the decisions made around us, and the invisible processes influencing our world. We’re already hooked on it, our attention spans shredded by its grip, and our collective health and sanity frayed by its creeping influence.

AI has evolved as a tool to allow us to make decisions stripped of humanity, with life-and-death consequences easily justified by dashboards and reports, and obfuscated by complexity and automation.

My career trajectory reflected the widespread commercialization of military AI and surveillance infrastructure technologies that has transformed our economy, politics, and way of life over the past few years. Following Donald Trump’s repeal of the Order on Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of AI — and his announcement of a $500 billion, data infrastructure investment fund led by Oracle and OpenAI — I want to help others outside of the industry understand what “AI infrastructure” is all about. To know what is at stake in a world where "citizens will be on their best behavior because we're constantly recording and reporting,” as Larry Ellison, co-founder and executive chairman of Oracle, put it recently.

Since leaving Palantir, I came to understand what the real-life consequences of the AI kill chain diagrams I illustrated looked like: bodies of children and civilians strewn across the rubble of hospitals, mosques, schools and UN facilities. I also saw several automakers I helped “modernize” come to be questioned by the senate for sharing private vehicle data with law enforcement without police warrants. Now I fear Palantir’s involvement in ICE deportations could help scale one of the most terrifying and ambitious projects of mass resettlement in human history.

I believe Palantir has been acting against its own Code of Conduct in its support of the IDF’s actions in Gaza and will continue to do so in supporting the U.S. Government, and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), in its deportation efforts. In particular, Sections B and C of Part I: Protecting Privacy and Civil Liberties — to Protect the Vulnerable and Respect Human Decency. Now, I want to test Alexander Karp and Palantir’s assurances that freedom of speech and civil liberties are important in order to widen discussion and awareness of unjust AI exploitation, and support and organize efforts that educate and advocate for people’s rights in an increasingly simulated and automated world.

Throughout the past year, after finally finding my way out of the industry, I continued to see militarized AI technologies leveraged here at home, on campus protesters in Columbia and Yale — including my friends — as they advocated for institutional divestment from weapons manufacturers and software companies working with the Israeli military. I know people whose families have been kidnapped by the IDF, and friends of my friends have even been shot in public just for wearing the Palestinian keffiyeh.

Meanwhile, Peter Thiel, founder and chairman of Palantir, refuses to address the role of his firm and its military technologies in enabling the genocide in Gaza, as attested to by Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and the independent experts of the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the occupied Palestinian territories. This has already led to institutional divestment, notably from Norwegian asset manager Storebrand, in fears the investment could put the firm at risk of violating local and international humanitarian law.

As a writer and designer, I believe that accessible critical discussions of the risks of AI need to expand and take over our media — as well as the promotion of outright resistance, deplatforming, and exploration of what it means to have a counterculture in the age of artificial intelligence. In my personal capacity, I’m working in hopes to unravel the harm I’ve done and to further a conversation that can escape the chokehold of nationalist and accelerationist rhetoric. Already, we have seen some of the most downtrodden populations subjected to the extreme technologies of surveillance, simulation, and targeting — the elderly, the people of Gaza, and through Palantir’s involvement in ICE deportations: immigrants in North America.

Palantir, Anduril, SpaceX, and OpenAI are now reportedly in talks to form a consortium to bid on defense contracts, meanwhile, Google has abandoned its pledge of not using its technology for weapons and surveillance systems. Next, Palantir’s CEO, Alex Karp — along with many other tech leaders and their political and business allies — will argue that we should become a “technological republic” and that it’s time we welcome the intervention of Silicon Valley startups into many more of our government and public institutions. Along with many other tech companies vying for a piece of the action, they stand ready to transform many of our democratic systems, government functions, and decision-making with largely unproven technologies reined in by few restrictions and controlled by the most powerful individuals in the world.

With the recent appointment of Gregory Barbaccia as the federal Chief Information Officer under the Trump Administration, a former intelligence officer and 10-year veteran of Palantir Technologies, and the upcoming appointment of another Palantir vet, Clark Minor, to lead data for Robert F Kennedy Jr.’s Department of Health and Human Services — policy and oversight for all of the federal government’s technology platforms will soon be heavily shaped and informed by these ideas and enabled by the repeal of AI guardrails.

What concerns me most today: seeing a new technocratic “broligarchy” take shape in Washington, D.C., watching Alex Karp describe the culture of Palantir as “Germanic” in a recent interview, and seeing him blatantly use violent, war-hungry rhetoric in support of his company and the kill chain doctrine. I also see the blueprints of Palantir’s strategic approach to business — sending young, “forward-deployed” engineers to fix and reconfigure systems — reflected in the work of Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), which has been caught recruiting Palantir alumni in private chats. Seeing Elon Musk himself perform something eerily close to a Nazi salute in excitement at the inauguration , only to see these developments unfold in the weeks after, have convinced me that this interlinked, big-tech movement is blatantly un-American and a threat to our peace and democracy. That it’s critical to share my experience in the hope that it will encourage wider awareness of the existential problems we face together as a country.

Professor Simon Prince of the University of Bath, author of several foundational deep learning textbooks, has argued that optimistic visions of AI should be met with caution and critical reflection, and that negative applications of AI would likely precede beneficial ones. He has appealed to scientists, researchers, engineers and communicators to take responsibility over the technologies they are bringing to market. Like Kate Crawford, Prince has warned of misleading claims, the risks of mass unemployment and un-skilling, and the need to hold AI companies responsible for their actions. He has also predicted a potential period of chaos before we have a chance to completely reorganize society under better principles.

First AI came to exploit the most helpless — but next: digital footprints and big data could be used to enforce abortion laws, directly threatening the rights of all women in this country.

The 1937 bombing of Guernica demonstrated the potential of air power to strike directly at an enemy’s civilian centers, bypassing traditional front lines, and leaving behind a trail of civilian casualties and suffering in its wake. Over the course of the past century, this doctrine evolved into the modern strategic bombing doctrine of the AI-powered kill chain, a doctrine which was extensively tested by the Israeli Defense Forces in their deployment of Palantir, Microsoft, Google, OpenAI, Amazon, among other data and surveillance platforms and services, to unleash the near-total destruction of the city as it stands today.

If we let these companies redesign and reshape every industry and function of government — according to their blueprint of data surveillance, modeling, and automation — then soon everyone will have a position in an AI kill chain. As builders of new systems, trainers of models, as users and executioners — but also as silent enablers, data points, or targets. We will all contribute to, and then become subject of, the decisions made by automated surveillance networks developed by corporate interests under a nationalist government.

As the conflict in Gaza shows signs of winding down, yet never reaching a resolution, no other use case of AI should be in the public spotlight more than that which was deployed there over the past year to devastating effect: that of killing human beings. Not only because of the destruction it has caused, and the big ethical questions it has surfaced, but because understanding the topic of the AI kill chain can help everyone understand the undemocratic revolution which has taken place over the past few years. One which tech companies have unleashed by turning the whole world into a system that can be modeled and automated — and you into a target.

Gaza today. Source: x.com

NB: This pamphlet letter, a protected creative work and essay, is addressed to the American people out of civic duty and concern and protected under the First Amendment. It is also addressed to my former employer, Palantir CEO Alexander Karp, two fellow alumni of the University of Pennsylvania, Donald Trump and Elon Musk, and the person that binds them all together: Palantir Chairman and PayPal Co-Founder, Peter Thiel. Thank you for revealing your intentions so honestly over the past few weeks, and thank you for your continued advocacy of free speech.

The people all said to Samuel, “Pray to the Lord your God for your servants so that we will not die, for we have added to all our other sins the evil of asking for a king.”

— 1 Samuel 12:19

Outstandingly brave of you. Thank you for doing your civic duty in revealing this existential threat. The good news is that AI chips aren't organic matter. While humanity still has control of the physical world we must decide to forbif AI chips from being developed or fabricated in factories until we can get some international laws.

Very brave and impressive! Thanks. I found Juan Sebastian Pinto's post today and a few weeks back found Yanis Varoufakis's book Techno Feudalism. Their ideas about current technology and it's effect on the trajectory of economics and society are very compatible. Good to see good ideas like these published.